A furor among several old-guard D&D creators prompted me to write this. Hyperbole, logical fallacies, and blinkered and outmoded thinking were on full display. Dismaying was the anti-progress and anti-sensitivity in evidence. So was the clear lack of understanding about modern gaming and games, including D&D as it exists today. Unsophisticated was the understanding of how communication and other shared experiences, such as streaming, affect gaming today.

Worse was a hidebound adherence to an outdated way of thinking about how games depict imaginary people. To these veterans, evil must be absolute so the good might discern and righteously smite it. The point here is not to vilify these guys for their shallow takes. I disagree with them, though. I’ll go into why, starting with the topic of recent discourse.

This discussion is about taking progressive steps with game content, especially about beings depicted as people. The controversy arose when the D&D team said it’s listening to the community and taking steps. Community members have written and spoken about avoiding painting imaginary people as universally evil. In D&D, they’re looking orcs and drow, among others. The conversation is also about avoiding the essentialism of racial ability score modifiers (as I covered here). Another branch is about giving imaginary people cultures complex enough to support the motivations a varied people can have.

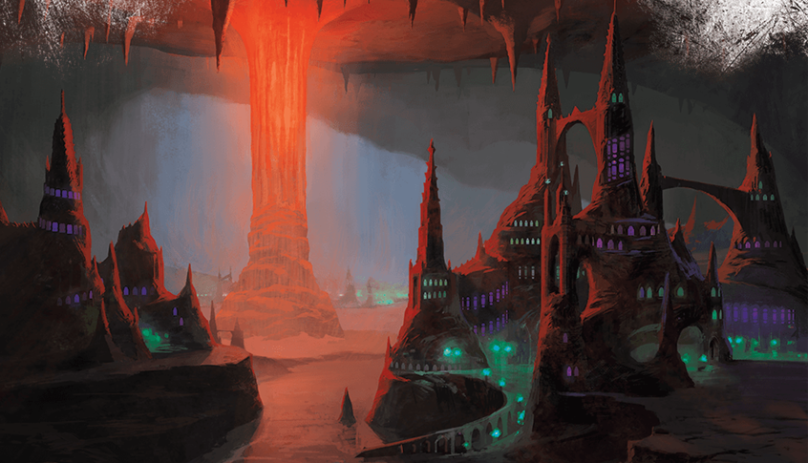

But this discourse goes further than D&D. Much further. It has included discussions of Tolkien, Lovecraft, the use of myth, cultural respect, and the employing of diverse creators. It’s a wide-ranging issue. For example, if we take Tolkien to task, despite his remarkable work, we must admit that the monolithic evil and othering of peoples other than those “of the West” aren’t the deepest or kindest takes. In some areas, Tolkien’s creations are incredible in their detailed (history, language, naturalistic description, the heroic everyman, and more). In others, the lack understanding, much as with the D&D old-guard (inherent evil, the othering of people “of the East” as servants of evil [see the image], the use of such stereotypes to create orcs, and so on). Still others lack refinement (monolithic evil, the nature and history of “evil” people and monsters, and so on). Important to mention here is that Tolkien also hated overtly racist concepts, such as segregation, and imperialism. He said so. And he included bits of anti-othering in his work. Also, unlike the D&D old guard, Tolkien had no way to access to later perspectives and the wide array of information we can now consult. As one of the pioneers in popularizing fantasy fiction, he had to do a lot of what he did in stark isolation compared to how one might create or learn about creation today.

None of the previous details are to apologize for where pioneers such as Tolkien (Howard, Gygax, and so on) fall short in their creations. They had biases or lightless corners in their thinking, as do we all. We can learn from these creators’ shortcomings, too. Learn about our own lightless corners and find ways to shine the light in, so we don’t repeat and reinforce those flaws. The D&D team seems to be ready to learn and move forward. Some D&D depictions, from Dragonlance to Eberron and Wildemount, already have. The next lightless corner awaits.

The way forward is understanding that many forms of fiction media benefit from nuances in the depiction of imaginary people. (Or suffer from their portrayals, as in the depressingly shallow urban-fantasy movie Bright.) Absolutist ideas, such as inherent evil in people, are harmful in that they can be injurious to those who suffer stereotyping in the real world. They also work against creating interesting characters, deeper scenarios, and compelling stories. Irredeemable foes are often the least noteworthy. Predictable traits make for dull individuals, whether in heroes or villains. This design also defies what we know about individual exceptionalism. Our myths, ancient and modern, heroes and villains, defy norms.

Also, more so in the age of rapid and wide communication, cultural objects are inherently political. They contain messages, whether the creators intend such meaning or not. Games are such cultural objects. And the stance of “no politics” is, without paradox, a political stance.

My original rebuttal took the form of a Facebook post that I decided to share as a Twitter thread. That thread got a wider reception than anything I’ve ever posted. That surprised me. I did the long Facebook thing to cover the bases I’d seen in the previous back and forth. I didn’t expect its length and tone to resonate so much out of its original context. I can’t say why it did. No one else has told me why in clear terms. But I’m glad it spoke to folks.

I’m preserving that thread here in block quotes. I’ve added some annotations based on the feedback I’ve received.

TL;DR. Creating complex imaginary people is better for play and design. It’s better for games as cultural objects and as spaces we learn in. (Play transmits values embedded in the tools of play.) Also, heroes consider the nature of their actions and their use of their power.

Significant among the feedback was the “you can play any way you like” truism. It’s so true, I thought that went without saying. But this thread isn’t telling anyone how to play. It isn’t saying one way of playing is superior to another. It is stating our tools of play send messages. We internalize the messages our play carries whether we want to or like it or not. It’s important, then, that our tools carry the messages we want and avoid the ones we don’t. We can improve our tools of play without sacrificing how we like to play. And there are lots of great ways to play, none of which these changes hamper. Having flexible tools improves our play and possibilities for play.

In a fantasy game, we needn’t treat a whole strain of people as evil any more we need to treat every human as evil. Every elf. Every dwarf. Every halfling. The belief that we do for escapist fun, heroics, or moral lessons is a misguided failure of imagination at best.

That failure of imagination is the failure to realize that others might receive different messages from the tools we use to play. Another failure is imagining that our way of playing is the only way to play. I’ve played roleplaying games in countless ways, from randomized light boardgame to emotional dramas. A tool meant for a diverse player base, as games such as D&D and Starfinder are, needs to be thoughtful in its treatment of beings it calls people.

We don’t need to depict whole races as evil for us to have games much like they are now. Why? I’ll use Nazis as examples in a heroic fantasy context. (And it’s a context still much simpler than the real world.)

Making nuanced people in our games is better for those games, no matter what your playstyle. This design strategy makes other fiction better, too. I don’t mind picking on Bright again here. It’s a great example of what not to do and parallels to avoid drawing. Bright is also a fantastic example of how easy it is to draw negative real-world parallels with the portrayal of fictional people. Bright is what you get when you shrug your shoulders and say, “It’s just an escapist fantasy movie. Don’t take it too seriously.”

Regardless, games are different from film and other fiction. But “make your game your own” and “change what you dislike” truisms aren’t a defense for allowing troublesome elements to remain in our designs whether for games or other media. Some D&D team members pushed these points as stopgaps while the team works on real fixes. Knowing many of these folks, they’re doing their best to make those changes. They care about the game and the community. They’ll change what they can. Keep speaking up about what you’d like to see changed.

1) The “Nazis don’t make all humans bad” rule. You can have evil humans (or Germans) without all humans being evil. Upper echelons in a society can be evil without the average citizen or folks in another society being evil.

This claim seems self-evident. And it is when we think of humanlike species in most games. It’s only when we get to monstrous or savage (loaded terms) beings that the moral latitude fades away. But it shouldn’t. If you’re creating people, give them the same consideration you give the normal and civilized (loaded terms) sapients. It’s always an option. Refinement in design doesn’t stop folks from ignoring that nuance in their games.

As designers, we can build complexity into our imaginary people. And we can build it in layers that don’t pile lore on new players. It’s my experience, though, that new players take “these are another kind of people” claims seriously. Confusing to them is when these claims contradict all the other evidence a game presents.

2) The “It’s okay to punch Nazis” rule. When members of a society are bad actors, it’s okay to smite the bad guys. When everyone’s steel clears the sheath, you don’t need to consider a bad guy’s moral character. See 6 and 9.

This point is key. It’s the point that proves my claim that these changes won’t change the way we play for the worse. Villains are villains. Heroic fantasy often involves smiting these baddies. And that’s okay. This place is where “it’s just a game” claims live and die. Live because it is just a game, and defeating the villains is fun and cathartic. Die, because those who claim adding breadth to imaginary people diminishes the game use this refrain. They’re wrong. The way they want to play, with definitive good and evil, is unthreatened by the change. The changes and this thread still say it’s okay to buy into and enjoy this “punch Nazis” conceit of heroic fantasy. See also points 7 and 14.

3) The “It’s not okay to punch the Nazi’s kids” rule. People associated with the bad guys might not be bad guys. Some are innocent. It’s morally reprehensible to harm and kill people guilty only by association. I get not wanting moral quandaries in your game about goblin kids. But, well, then don’t put goblin kids in the goblin bandit camp.

I get not wanting moral quandaries in your game about goblin kids. Well, then, don’t put goblin kids in the goblin bandit camp. If you do, you’re inviting the quandary. That’s on you.

These speak for themselves. Don’t put kids in harm’s way if you don’t want the moral implication of that in your games. Video games and other media remove kids, don’t place them in harm’s way, or make them invulnerable. Few complain.

4) The “Some Nazis went to prison” rule. It’s also okay to capture bad guys and see them tried for their crimes. Killing doesn’t have to be the end of any clash with villains. Even the worst ones.

Defeating baddies doesn’t have to mean killing them. Some games and stories have the consideration that the protagonists can’t kill for some reason. Such games are still fun to play. Those books, comics, and films are still fun to consume.

5) The “Germans were liberated from the Nazis, too” rule. When a bad regime falls, the people that regime oppressed have the opportunity for their society to change. They no longer suffer the evil.

The point here is that removing evil frees those suffering from evil, especially in the simplified worlds of heroic fantasy. This is where “The Menzoberranzan Resistance Needs You!” campaigns live. Talk about a world-shaking drow game. Intrigue, espionage, subterfuge, and knocking demon heads. Underdark ancestries only. Freedom!

6) The “Humans are more complex than their Nazis” rule. Having complex peoples opens the design space and allows for more and more interesting stories. Stories of liberation, stories that defy expectation, stories of understanding, stories of “the righteous” wronging “evil” people, stories of heroes being heroic in more ways than merely smiting evil.

I’m going to come clean—I love stories of rescue, liberation, and redemption. I also love turning assumptions on their heads. I’ve even considered an epic adventure that ends with redeeming Asmodeus.

7) The “Anyway, we still got Nazis” rule. Even with complexity espoused earlier, you still have bad guys, and plenty of them. Cruel human bandits. Hateful elf-superiority fascists. Remorseless orc raiders. Bloodthirsty goblin theocrats. (Bree Yark for Maglubiyet!) Ruthless hobgoblin warlords. Nihilistic apocalypse cultists. We’re not short on potential foes.

Driving home the point that we still have plenty of villains when most of the villains are people. But we have room for true monsters, too.

8) The “The Nazis aren’t the only problem” rule. Building on 7, plenty of evil beings exist that aren’t people. Other creatures are destructive or predatory. Like other villains, they must be stopped. Some of these problematic creatures and villains aren’t evil.

This point is the “xenomorph principle” I take from the Aliens franchise. No one stops to consider the moral character of the xenomorphs because, foremost, they’re dangerous predators. They’re also not presented as people. Number 11 expands on this point.

9) The “Nazis are people” rule. Even though when the war is on you might not need to consider your wicked foe’s moral character, it can be interesting if you do. Doing so shows your own moral character. That’s what makes heroes shine—considering the personhood even of their adversaries.

The most upright heroes avoid killing. They know the use of their power can result in harm and death. And they feel remorse when forced to kill. But they’re willing to do so for the greater good. These paragons of virtue make great storytelling devices. They also make for challenging characters to roleplay. This part of the discussion reminds me of the alignment picture from the 1981 D&D Basic Set, included here. At ten years old, I understood this image.

10) The “Being better than a Nazi doesn’t make you righteous” rule. Real heroes, the truly righteous, consider the meaning and ramifications of their actions. They consider the moral context of their own behavior and power.

Some of the best stories come from mending misunderstandings or finding common ground with potential foes. You know, solving the real problem instead of just beating one side into submission.

Someone said this point is a weak point, but I don’t think so. I aimed at the idea, presented by the old guard among others, that smiting evil is a virtue in and of itself. A virtue of character and games of good versus evil. I disagree. Any sumbitch with a sword can kill monsters. So smiting evil is a small virtue if it is one at all. (Intent matters.) It takes a real hero to apply wisdom to a situation and choose the hard path of finding and solving the real issue. Part of the richness of Geralt’s character in The Witcher (books, games, and show), what makes him a hero, is his willingness to put himself at greater risk to solve the real problem. He has the power to smite the “apparent” evil, but he chooses to look deeper. And he makes mistakes when thrust into the role of judge, jury, and executioner.

11) The “Nazis aren’t aliens or devils” rule. Supernatural evils, such as demons and some undead, are often described as absolute. That can mean sapient but supernaturally evil creatures, such as many demons, exist in a moral space irreconcilable to those of mortals.

That’s true of alien moralities. Mind flayers in D&D fall into this category. However, myth and fiction show us fallen angels, rising devils, and communication gaps crossed. Nuance in these creatures still provides flexibility that’s good for design and play.

Irreconcilable differences are a cornerstone of conflict. We don’t need “evil” to have conflict. Having differing or competing goals is enough. I mean, no player wants their character to be a xenomorph incubator, as in Aliens, or a mind flayer thrall, like you might in D&D.

12) The “Nazis aren’t automatons” rule. Zombies, constructs, and other automatons often fall outside morality. Such creatures not only aren’t people, they often have no personal will. They’re controlled. Controlled by a villain, they are foes who aren’t people.

They also provide a way you can have foes that require no moral considerations when you fight them. They’re automatons, not people. Some creatures that used to be people exist in this design space, such as the darkspawn in Dragon Age or typical zombies.

Robots are a classic foe in kids shows for this reason. You can blow up a robot without remorse. Doing so isn’t killing a person. It’s less morally reprehensible for a villain to use automatons as an ablative shield, too.

But even Dragon Age wonders if the darkspawn can be saved. If the archdemon might be freed. Moreover, if the real problem, the pollution of the spirit world, can be fixed? And other works wonder if sophisticated automatons are people. It’s a question one might ask about some elemental bindings in Eberron, given the personhood of the warforged.

13) The “Fantasy Nazis have mythic archetypes” rule. Imagine the Nazi god. A demigod leader. Nazi necromancers and diabolists raising undead or fiendish hordes. Also, what if from within Nazi-oppressed lands rose a folk hero, an ally to other heroes?

A great question in the thread asked if the reworking allows for mythic archetypes. If anything, the changes allow for more. When imaginary people have diverse and complex cultures, the mythic options are more diverse. Possibilities expand. As they do when depth allows flexibility and options.

Mythic possibilities are plain in modern fiction that fits with our game experiences and adventures. Take the Thule Society and its part in the rise of the Nazis. Hellboy’s originates in the mythological treatment of that real, occult, and sinister group. Nazis and their occult preoccupation appear in plenty of other heroic fiction. In most of that fiction, such as Raiders of the Lost Ark, the heroes punch the Nazis. Like in that fiction, the baddies in our games and fiction don’t have the limitations of the real world. Only the game rules and our imagination limits the evil, mythic reach of our villains.

14) The “It’s okay to like punching imaginary Nazis” rule. Our heroic fantasy, from Lord of the Rings to Star Wars, uses violence to resolve conflict. It’s okay to enjoy the fiction and the play. I’m not decrying that. Nuance in imaginary people still allows for that.

This place is where the statement “it’s just a game” has broader validity. That statement loses validity when dismissing content others find uncomfortable or objectionable. We can have complex imaginary people in design and still enjoy the game our way.

This place is also where “you can alter the game to suit you” has the most validity. If the tools of play offer breadth, those playing can choose how to apply that freedom. Less flexibility is more prescriptive, more restrictive on play.

Some folks had crises of enjoyment after reading and discussing the thread. If our imaginary foes are moral beings, then killing them could be wrong. It feels bad. I’m sorry my words caused any distress. But that’s a mature approach to this sort of play. You experience a richness when you choose what your character does, knowing that the choice says something about the character. Is your character willing to be that judge, jury, and executioner? Are they willing to risk life and limb to find the truth rather than the easy path?

This leaves aside the question of respect for other players. It’s also up to mature players to make sure their character choices don’t do real harm to others or their enjoyment of play. To me, that’s the line. It’s one saying “that’s what my character would do” doesn’t save you from if you cross it.

But nothing is wrong with treating a game such as D&D as a tactical board game. It works great in that context. And it can be super fun that way, peeling off most considerations, crawling through a random dungeon, and beating up monster-shaped bags of hit points. At Gen Con in 2008, I did just that with friends one late evening. Random dungeon tiles, a stack of monster cards from the minis game, characters, and dice. Silly fun.

And the game works fine in plenty of other play modes, from that tactical silliness to higher drama. Other games provide for some playstyles better than D&D does, too. That’s because they have tools D&D might lack. And having sophisticated elements, such as complex and considered imaginary people, only expands the play options. It doesn’t diminish them.

Let’s all work together to make and run better games.

And by run here, I mean running games where everyone at the table feels welcome and comfortable, respected. If our tools of play help that along, all the better. Well-designed imaginary people are one of those tools.

Support me on Patreon or Ko-fi if you like what I’ve done here or my other work and publications. Support allows me to keep working on essays such as this one, along with other side projects you can access on Patreon.

Top photo by Holger Link, next image from The Return of the King film, orc images from the Bright film, Lady Slaps Nazi from Francesca Berrini and Unusual Cards (where you can buy that image on a card!), next image is Menzoberranzan from Out of the Abyss, next image the Alignment illustration (by David S. LaForce) from the D&D Basic Set (1981), next image as captioned from Aliens, next image from Hellboy comics, and the final photo is Henry Cavill as Geralt of Rivia.

[…] of why I do like them or what I want them to become. But I wrote this one as a supplement to my blog on imaginary people. I did so not because this piece is at all timely, but because a good friend skilled in literary […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] has graciously agreed to allow me to republish his comments here as a guest article. Chris has also published an annotated version, which I highly recommend you go check out on his blog. I have faithfully reproduced his original […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you expansed the original thread, as I did not entirely understand everything you were saying there. This post helps enormously. By the way, can you do a specific critique of Bright? You invoke it a couple of times here, but never get specific about how it’s treatment of orcs is bad or how it’s an example of “what not to do.” Especially when the film seems to be -trying- to present orcs in a sympathetic way. Tell us what they did wrong?

LikeLiked by 2 people